Equity and innovation: Typically isolated

Hosted by UNC Wilmington’s Watson College of Education, the 2nd annual Making Innovation a Priority in NC Schools conference brought together policy makers, K-12 educators, administrators, consultants, coaches, higher education faculty, business representatives, and students to highlight innovative programs and practices in K-12 public education in North Carolina. A main goal of the conference was to build capacity for how supporters of education can capitalize on innovation as a way to improve schools.

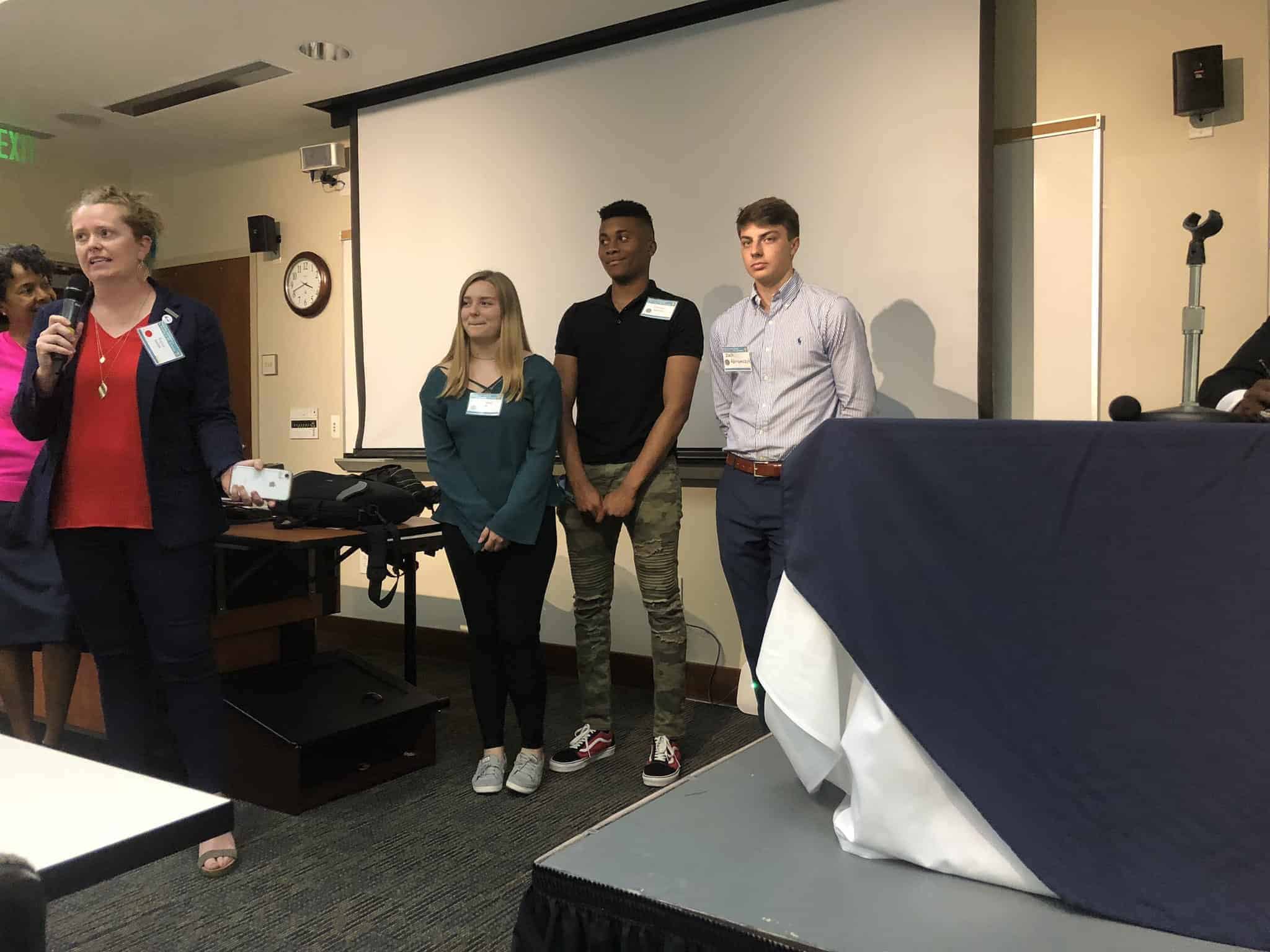

Immediately following the conference, some attendees also participated in an interactive discussion on the state of racial equity in North Carolina. This education equity gallery walk was led by State Board of Education member James Ford, EducationNC’s EdAmbassadors, and a team of students from the Wake County Public Schools Office of Equity Affairs.

While these events may appear exclusive of one another, in reality, their purposes should be inextricably linked. How then, we might ask, are innovation and equity related? In this article, I will provide a brief overview of both, as well as where overlaps exist. Finally, I will offer suggestions on how we might balance these two fields that typically exist in isolation of one another as we seek to continually improve our schools.

Conceptualizing innovation

As an assistant to the primary conference planner, I have spent the last two years analyzing the term “innovation” within diverse educational contexts. What does this concept mean? What does innovation look like at the national, state, local, school, and classroom levels? How do ideologies impact the interpretation and application of the term?

“Innovation” is paradoxically as complex and watered down as overused buzzwords often become. At its core, innovation represents a paradigm shift; a disruption of the status quo; any new idea that is defined by outside-of-the-“this is how we’ve always done it”-box thinking. Pedagogically speaking, innovation is grounded in experiential learning methods such as project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, service-based learning, etc. that are not confined to the traditional four walls of a school and which often give power to students to solve real world problems.

In the career and technical education field, educators and supporters of education (typically from the business realm), see innovation as synonymous with entrepreneurship in schools and developing entrepreneurs and trades workers of our students. For some state leaders, innovation is referenced in relation to personalized learning. Of course, technology contributes largely to the innovation conversation (think coding, gamification, virtual and augmented reality, just to name a few). There is also the open source movement, which seeks to encourage collaboration via open resources and technology.

In an age of academic accountability via standardized testing, programs and practices that prioritize relationships and interpersonal skills are even innovative. Many call the Advanced Teaching Roles initiative innovative simply because it is a restructuring of the teacher’s role that is not “how we’ve done it before.” As you can imagine, this list is not exhaustive. Review the 28 Innovation-in-Action Exhibit teams that shared information with conference attendees as a great resource of some of the above examples. What is crucial is that we define our innovations clearly. It is important that we have a common language when discussing innovation in education.

State support of innovation

There are also examples of how the state has sought to support innovation through legislative changes. One was through charter schools. The original intent of charter schools — because of their flexibility in regulations and accountability — was to encourage creative teaching methods and share best practices with traditional public schools. They were to serve as hubs of innovation, so to speak.

Additionally, just this past year, the entire Rowan-Salisbury School District was given charter-like flexibility by the State Board of Education. In 2018, 60 schools in North Carolina joined the Schools that Lead pilot program to address three specific problems of practice. Schools and school employees use improvement science to collaborate within their Networked Improvement Communities in the pilot. Again, all of these together are just a few examples of how innovation is perceived in public education in North Carolina’s public schools.

Framing innovation with purpose

The Innovative Schools Network (out of Wisconsin) identifies seven areas for innovative practice (pedagogy, curriculum, assessment, school design, governance, scheduling, and relationships). These have helped to guide our thinking around innovation in education so that it is not such a broad, easy to repeat buzzword, but rather a term with guidance for specific impact on problems of practice in schools. We have used these areas and their examples in the last year as the Educational Innovation Network NC, made up of 2018 conference attendees and educators from across the state, and which has expanded its reach in an effort to increase the frequency of conversations around the term and context of innovation.

Equity in education via innovation

This spring, while participating in planning the conference, I was enrolled in an equity literacy course in my curriculum and instruction doctoral tract within educational leadership at UNCW. The more I learned about being an equity literate educator, the more tension developed and I began to question my work around innovation. I realized I rarely heard people discuss the two terms together. Sometimes innovation seemed to occur just for the sake of innovation, or for the sake of student outcomes without any regard for the opportunity gaps and inequities that we know many of our students, families, and school communities face. I started to ask how we could be more intentional about integrating aspects of equity and equitable practices into the planning and design for the innovation conference and future work.

According to one educational equity expert, Paul Gorski, being an equity literate educator means that we position the marginalized and oppressed identities of our students in the center of our decision making. It means we reject the deficit views that focus on “fixing” marginalized students rather than addressing the conditions that marginalize students. Being equity literate means recognizing, responding to, and redressing biases and inequities when we see them, and then developing sustainable learning environments that are equitable for all students and families. This is where innovation and equity fit together.

As attendees at the education equity gallery walk read the data points on racial inequities among North Carolina students, they also heard directly from students of color about their personal stories related to the data. This was powerful. The innovation process begins with empathy. We have an opportunity to use our data and ongoing reflections around racial inequities to develop deeper empathy into all other forms of student identities. This includes (dis)abilities, language, mental health status, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, immigration status, poverty level, etc.

Empower students to solve problems

The best way to do this? We need to ask our students. This represents the truest disruption of the educational status quo. In our classrooms, schools, districts, and at the state level (including the state Department of Public Instruction, the State Board of Education, and the General Assembly), we need to be intentional about elevating students’ voices to guide our innovative improvement processes. Such lofty goals require that individual practitioners, policymakers, business and community representatives, and school and district networks recognize the moral imperative to not simply innovate, but to innovate with the intention of improving equitable practices and experiences for all students by not merely including them, but by supporting them in leading.

Moving forward

Expect the vital work that the Leandro commission and the My Future NC commission are undertaking to establish clear directions for the future of North Carolina’s educational improvement. Our hope in developing this conference and the Educational Innovation Network NC is to support the networking and development of cultures of innovation and collaboration across North Carolina.

Whereas cultures of compliance and competition will perpetuate inequities, cultures that are collaborative, reflective, iterative, and innovative — and which genuinely include our youth — will perpetuate improvement and equity for our students’ sake.

If you are interested in being involved in the work of the Educational Innovation Network NC, contact Robert Smith at smithrw@uncw.edu, follow @InnovateEduNC on Twitter, or contribute to the conversation using #Innovate2EducateNC.