In the history of North Carolina’s programs for struggling schools, Restart has a short track record. The program began in its current incarnation in 2015 and allows continually low-performing schools to operate with charter school-like flexibility.

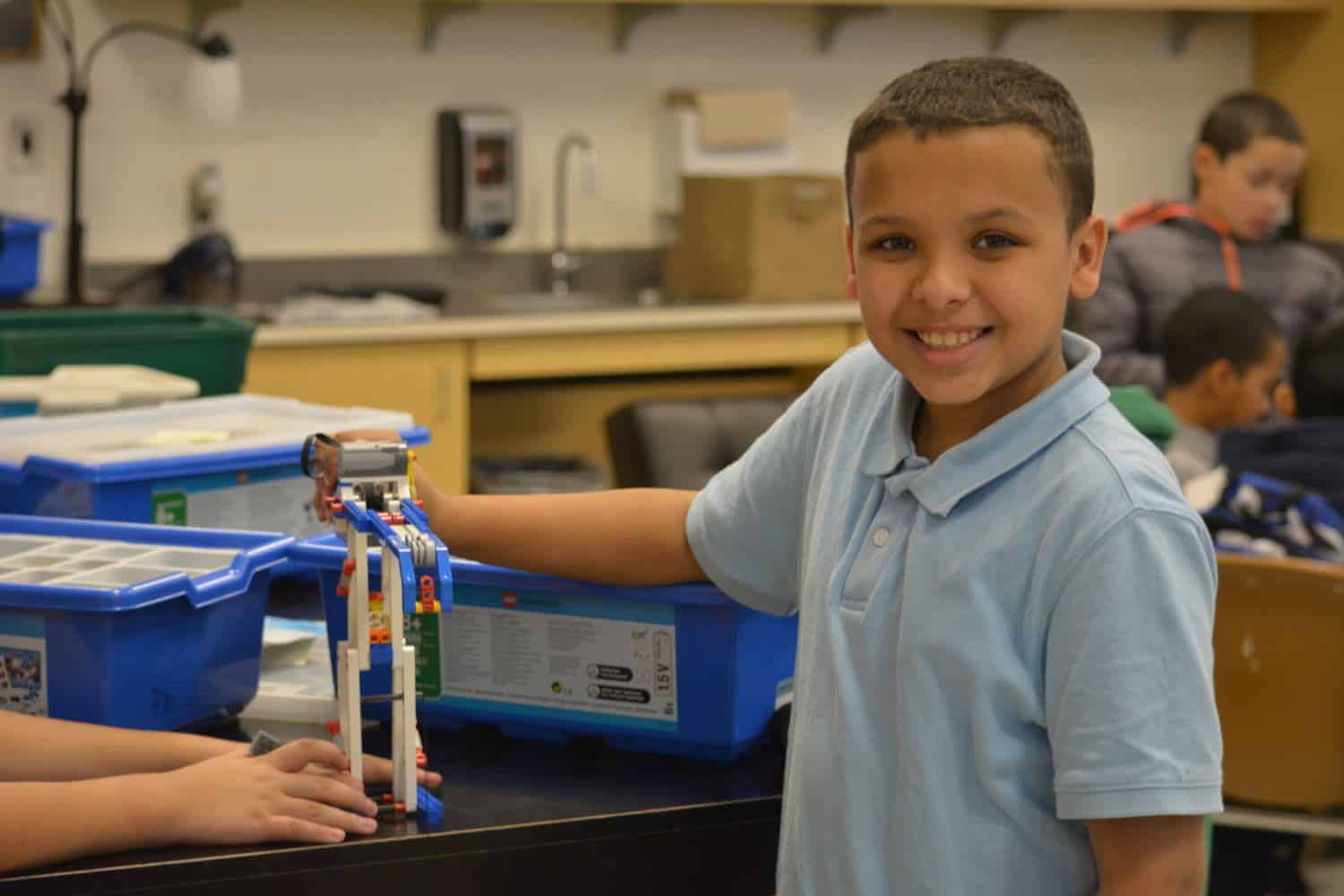

With their newly granted freedom, some schools have hired more teachers, lengthened their school day, reduced class sizes or started after-school clubs. Though the program is in its infancy and there is no performance data yet, some state leaders are already asking: Is this flexibility the future of public education in North Carolina?

The first schools to operate under the Restart model began the program in the fall of 2016. While the number of schools who gained approval to use the program increased dramatically — 103 and counting — there is no way to know yet whether what they are doing actually helps their struggling students.

In a state where many education decisions are made by the General Assembly in Raleigh, Restart is an aberration: a statewide program basically created by local school districts. The oddity does not bother Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union. He favors districts coming up with their own ideas.

“This is exactly what we in the General Assembly are looking for,” he said. “We need to depend on the experts in the field to come and say, ‘We’ve got an idea.’”

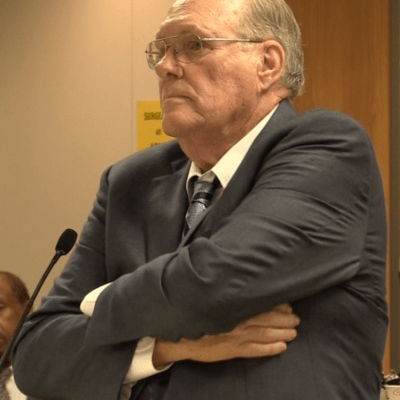

Others, like Rep. Jeffrey Elmore, R-Wilkes, are more skeptical. His primary concern is accountability. Can a Restart school putter along for a decade without a measurable change in outcome and retain its charter-like flexibility?

“What is the endpoint?” he asked. “What timeframe do we give you to try to achieve improvement?”

Those are questions the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction is trying to answer. As most Restart schools near the end of their first full year, the state is watching and waiting. As it stands now, schools can be part of the Restart program indefinitely.

“There’s no exit criteria because Restart is not imposed on schools. It’s their option,” said Nancy Barbour, North Carolina’s director of educator support services.

The State Board of Education has the right to revoke a school’s Restart status for lack of progress, poor implementation or for a range of other issues, but that has not yet happened. Board Chairman Bill Cobey said he is still learning about the program but has heard positive reviews.

“I think the fact that we sign off on them, we are confident that we have very good professionals out there in the field, and it’s about trusting them and giving them an opportunity to innovate,” Cobey said.

The Board relies heavily on Barbour and her team for guidance on selecting low-performing schools to approve for Restart.

“If it gets through Nancy, it’s probably going to be approved by us,” Cobey said. “We have so much confidence in Nancy and her ability to evaluate and screen these plans. If she’s comfortable with it, I think there’s almost a 100 percent chance we’ll be comfortable with it, too.”

As the program continues to grow, Cobey said, he has some questions for the schools participating, including what barriers they have encountered while launching the program and any other challenges they have faced.

“That would be extremely interesting to me,” he said.

This fall, data from the first year of implementation will be available. School leaders will watch closely. How will Restart schools be judged and held accountable? The answer is unknown for now, but Barbour plans to present some options to the State Board this summer.

State education leaders already examine the schools’ testing data — that is how they determined the schools were low performing — but it is unclear how the state will measure the effectiveness of techniques the schools are trying, such as class-size changes, calendar shifts, or after-school clubs.

If students do not improve test scores or other more measurable goals, Barbour said she will set up a system so schools can report other ways they have improved. The difficulty, she says, is how to measure improvement without hard data.

“So, for instance, I think it’s fantastic that a school has cut their discipline referrals in half. I’m just using that as an example,” she said. “You’ve got less discipline problems because of something you’re doing in that school, but is that in fact improving education for that child? And how long will it take for that to improve education for that child?”

Barbour said she would like for schools to examine small groups of children who are struggling the most to determine whether they are making any progress as a result of the school’s Restart program.

“This is going to give schools an opportunity to find data points and dig deeper into their data to find out, well, why aren’t these 25 students making progress and what are we going to do in our flexibility to address those students?” she said.

Diving deeper into the data will help schools identify specific areas where students are struggling.

“It’s about subgroups of students and it’s about progress for those subgroups, but it’s also about groups of students that show patterns of failure and groups of students that show patterns of success and then being able to make changes within your school that address those changes,” Barbour said.

Assuming the state finds a way to measure Restart’s effectiveness, and the schools involved show progress, questions remain. Should flexibility be expanded to more schools in North Carolina, including those that are higher-performing? While some say yes, others are skeptical.

The future of flexibility

Jim Merrill is the former superintendent of the Wake County Public School System and the chair of the first board of superintendents for The Innovation Project (TIP), a group of district superintendents, staff, and collaborators working on education innovation in North Carolina.

If Restart schools show an ability to improve performance for their struggling students, then Merrill believes local flexibility should be expanded. But whether it should be and whether it will be are two different questions.

“You would think that the preponderance would say, ‘Let’s go. This can work.’ I’m still sort of optimistic like that,” he said. “But we’ve been bruised a lot over the years, so we would have to wait and see.”

What Restart is doing in North Carolina is not entirely unique. Several different programs and schools in the state have flexibility. Charter schools are the most prominent example, but schools chosen for the state’s new Innovative School District, or ISD, will also have greater flexibility.

The ISD will include five of the state’s lowest-performing schools as part of a new school district overseen by Superintendent Eric Hall. The five schools will be managed by outside organizations, which could include charter and education management groups.

Those five schools will have flexibility. Alternatively, districts with a school in the ISD may also create so-called Innovation Zones which also grant schools flexibilities.

Through the ISD, Innovation Zones, Restarts, and charter schools, a trend is emerging.

Gregg Sinders, the North Carolina director for charter school network TeamCFA, said he does not understand why, under Restart, only recurring low-performing schools get flexibility.

“If it’s good for low-performing, why isn’t it good for all?” he asked. “The foundation of my belief is that I think every traditional public school ought to have charter-like flexibility.”

Hall, the ISD superintendent, strikes a more cautious note. He points out that Restart and the ISD began around the same time. Part of the ISD legislation exempts schools that adopted a reform model, such as Restart, from ISD selection.

“I think districts started to look at what are the other things they could do on their end to look at flexibility,” Hall said.

Rep. Elmore had a more explicit take on the relationship between the ISD and Restart.

“I think the reaction of a lot of the Restarts was, let’s just go ahead and do this because we have an intense fear of the ISD,” he said.

As the person who oversees Restart, Barbour believes some schools may have applied for the program to avoid being selected for the ISD.

“No one has written that on their (Restart) application,” Barbour said. “But I have had many conversations that have asked me, ‘Is it true that we wouldn’t qualify for the ISD?’ So, I would have to say yes, I believe, with no empirical evidence, but I do believe based on conversations I’ve had that some people have submitted applications to do just that.”

Durham Public Schools recently removed 12 of its schools from the Restart program, citing concerns with launching the program in that many schools while dealing with the potential costs of K-3 class-size reductions.

But Durham left two schools in the program: Glenn Elementary and Lakewood Elementary. Those schools were considered last year for the ISD, much to the displeasure of the Durham Board of Education which fought the possible takeover.

One of the reasons Durham decided to keep Glenn and Lakewood enrolled in the Restart program is that it prevents the state from trying to pick them for the ISD, according to Nakia Hardy, Durham Schools’ deputy superintendent for academic services.

“It was part of the decision,” Hardy said. “We also looked at the data and talked with the principals, so that we could make a very thoughtful recommendation.”

The ISD superintendent said he is taking a slow approach with the program to make sure it is implemented correctly, and he thinks Restarts should do the same. However, he says, flexibility is not necessarily going to fix every student’s problem.

“Flexibility can be great, but if flexibility alone was the silver bullet then we would never have a low-performing charter school,” Hall said.

Despite that, Hall is optimistic about Restart.

“I think looking at how it’s happening here in North Carolina, to me that’s a positive thing,” he said. “The best reforms happen close to the community.”

Although Restart has the support of odd allies, Merrill takes a bleak tone when considering the concrete future of school flexibility in North Carolina.

“I think our flexibility could be at risk because we’re the big, bad public K-12 gorilla, and we need to be regulated more,” he said.

The attitude of the legislature is to regulate more, not less, Merrill said, and giving schools local flexibility would mean relinquishing some power.

For one lawmaker, Sen. Jerry Tillman, R-Randolph, that is not a problem. He has advocated many times over the years for more flexibility for schools, and he reiterated the point at last week’s Joint Legislative Task Force on Education Finance Reform.

He said he hears from schools across the state that they need and want more autonomy. School leaders are close enough to the ground to know how best to deploy resources, he said, and they should have the power to do so.

“When we wake up one day and have this type of funding, we will have better schools,” he said.

Rep. Hugh Blackwell, R-Burke, agrees with many others that flexibility is needed. But whether lawmakers will grant it is another question.

“The challenges are that it’s one thing from a state perspective to give flexibility, but nobody at the state level is going to be prepared to walk away and say, ‘Hey, whatever you do with it, that’s fine with us,’” he said.

Rep. Horn says lawmakers often “talk out of both sides of our mouth” when considering whether to give districts more control. On one hand, legislators discuss the need for decentralization but then mandate what districts can pay and teach, and when they have to start and stop the school year, he said.

“We need to get our act together at the General Assembly and decide which way we’re going,” Horn said.

However, there is a fundamental need for the state to know how programs are working, according to Horn, who said districts often will not admit when something is not working. Instead, he says he hears “excuses.”

That will not work for the legislature, Horn said, because there has to be some sort of consequence for Restart schools if they do not improve. Without penalties, all the state will get is “mediocrity,” he said.

Sinders, state director for a charter school network, has a different take on accountability for Restart. He thinks they should be held to the same standard as charters.

“You can have charter-like flexibility as long as you take charter-like accountability, up to and including being shut down,” he said.

Charter schools are required to periodically appear before the state’s Charter Schools Advisory Board to have their licenses renewed. If they do not comply with certain requirements — like meeting academic and operational standards — they may face closure. Sinders believes Restart schools should be moved under the authority of the Office of Charter Schools and follow a similar system, including having applications run through the advisory board instead of going directly to the State Board.

Ann McColl, CEO of The Innovation Project (TIP), said accountability already exists in the form of local boards of education. Restart schools are under the umbrella of their local districts even after gaining flexibility. If they are not successful, the local boards have authority to step in.

Regardless of how the state holds Restart schools accountable, it is too early to tell how they are doing, according to Sinders.

“You have to let the cake bake. It’s not fair to say it’s working or isn’t working,” he said. “I just think there has to be some check-in at some point.”

Restart advocates say they are not opposed to accountability. They assume it is coming. But at present, they are focused on getting set up and running. Joe Ableidinger, chief program officer and director of innovation for The Innovation Project (TIP), said the reaction to Restarts “will and should come” in a year or two when a lot of schools finally have results to show.

In the meantime, it is up to Barbour and her educator support services team at the Department of Public Instruction to figure out how it will all work.

“It keeps me up at night, I will say that. Because I feel like we have to give schools every opportunity to show progress, but then at some point we have to say, it’s still not resulting in improving academics for kids, and that’s where it’s tough for me,” Barbour said. “You know, when do you make that call?”

This story was reported by EducationNC reporter Alex Granados and WRAL reporter Kelly Hinchcliffe through a collaboration funded by the Center for Cooperative Media. EducationNC data reporter Lindsay Carbonell contributed to this report.

Editor’s Note: Gerry Hancock, a co-founder of The Innovation Project, is also one of the founders of EducationNC.