Part I: Public School Forum declares book closed on Common Core, whistles past many shortcomings

In his article “Maintaining rigor and listening to teachers in the debate over academic standards,” Keith Poston argues against revisions to the current Common Core standards and the importance of ensuring teachers have a voice in this discussion. In a two-part response, I argue, in part one, that significant changes are needed to the standards, and, in part two, that teacher surveys can provide important information – as long as the instruments are valid and reliable.

“Maintaining rigor and listening to teachers in the debate over academic standards” is an article by Keith Poston, President and Executive Director of the Public School Forum, that recently appeared on the website EducationNC. Poston thinks members of the Academic Standards Review Commission (ASRC) – the Commission established by the North Carolina legislature to review English and Math Common Core Standards – need to be reminded of what he believes to be the potentially harmful consequences of their actions. And Poston urges ASRC to heed his warnings.

Keith Poston is a friend. However, that friendship doesn’t stop me from saying I strongly disagree with the comments he made on both topics, comments that I believe to be wrong and misleading.

Shouldn’t all students be held to the same standards? That’s a question Poston rhetorically asks readers in response to comments made by Jeannie Metcalf and Tammy Covil, two ASRC members who made comments that imply students of lesser ability may not be able to achieve some of the higher-level expectations of the Common Core. Both Covil and Metcalf have questioned whether certain standards were age-appropriate. Poston fears that if the Common Core Standards are not right for all students, any changes will automatically result in standards that are less rigorous and challenging.

In my opinion, Poston is not asking the right question. His concern for high standards might on first blush be admirable. However, such a view presents a one-size-fits-all view of education that denies differences in background and ability. It also ignores the larger and more significant issue with which ASRC must wrestle: Are the Common Core Standards age appropriate?

Poston falsely believes changes by Commission members automatically lead to a decline in rigor. Rigor – properly understood – assumes age-appropriate materials and instruction. If Commission members fail to fully consider rigor and age-appropriate instruction, they are failing to fulfill their responsibilities.

Session Law 2014-78 established the Academic Standards Review Commission. ASRC was established to:

Conduct a comprehensive review of all English Language Arts and Mathematics standards adopted under G.S. 115C-12(9c) and propose modifications to ensure that those standards meet all of the following criteria:

a. Increase students’ level of academic achievement.

b. Meet and reflect North Carolina’s priorities.

c. Are age-level and developmentally appropriate.

d. Are understandable to parents and teachers.

e. Are among the highest standards in the nation.”1

Notice the legislation specifically states the commission shall “conduct a comprehensive review.” The legislation continues ASRC is to “propose modifications to ensure that those standards . . . are age-level and developmentally appropriate.”

Implicit in such a review is addressing the question of whether existing standards are appropriate for grade, age and ability levels.

I agree with the statement that all children, no matter their background, can learn. However, I also believe the current review process must determine whether the Math and English Common Core Standards are the best tools for educating students.

Many people believe the Common Core standards – while they may aspire to a laudable goal – have significant problems. Keith Poston questions commissioners who raise concerns about whether students can meet the standards laid out by Common Core. Mr. Poston and other Common Core advocates believe children should all be treated the same and be held to the same standard.

Anyone familiar with the public discussion over Common Core knows that one of the major criticisms parents, teachers and other educators have about it is that many of the standards are not age-appropriate. This is particularly true for the early childhood grades, K-3.

It’s a criticism Common Core advocates have successfully avoided. Still, it bears repeating, especially, in light of Poston’s claim “Common Core foes want badly to avoid engaging directly with the current standards.”

A statement could not be more wrong. As time is limited, let’s talk specifically about criticisms surrounding the K-3 Common Core Standards. Two articles in the Washington Post (see here and here) help to summarize the major criticism of the K-3 Common Core Standards. In one, education experts Edward Miller and Nancy Carlsson-Paige wrote:

When the standards were first revealed in March 2010, many early childhood educators and researchers were shocked. “The people who wrote these standards do not appear to have any background in child development or early childhood education,” wrote Stephanie Feeney of the University of Hawaii, chair of the Advocacy Committee of the National Association of Early Childhood Teacher Educators . . .

The promoters of the standards claim they are based in research. They are not. There is no convincing research, for example, showing that certain skills or bits of knowledge (such as counting to 100 or being able to read a certain number of words) if mastered in kindergarten will lead to later success in school. … At best, the standards reflect guesswork, not cognitive or developmental science . . .

Moreover, the Common Core Standards do not provide for ongoing research or review of the outcomes of their adoption—a bedrock principle of any truly research-based endeavor.

If the standards are so great, why wasn’t a single person of the 135 people on the panels who developed the K-3 Common Core Standards a teacher or early childhood professional? Such oversights are hard to understand, especially in light of the repeated claims that those who developed the standards had constant feedback from teachers and education professionals.

In March 2010 more than 500 early childhood professionals signed the Joint Statement of Early Childhood Health and Education Professionals on the Common Core Standards Initiative. The statement read:

We have grave concerns about the core standards for our young children… The proposed standards conflict with compelling new research in cognitive science, neuroscience, child development, and early childhood education about how young children learn, what they need to learn and how best to teach them in kindergarten and the early grades …”

There is little evidence that such standards for young children lead to later success. While an introduction to books in early childhood is vital, research on the links between the intensive teaching of discrete reading skills in kindergarten and later success is inconclusive at best.

The experts went on to call on the National Governors Association and Council of Chief State School Officers – the two organizations who help to develop and implement the Common Core Standards – to suspend the drafting of Common Core standards from kindergarten through grade three. Obviously, that hasn’t happened.

Members of the early childhood profession spelled out other objections to Common Core in a document called Defending the Early Years. Briefly, the document asserts CCSS is not supported by substantive research, fails to take into account what children need (i.e., play and good teachers), and falsely implies that CCSS will counteract the effect of poverty and help to create equal opportunity for all.

Most recently project scholars associated with the Defending the Early Years Project published “Reading Instruction in Kindergarten, Little to Gain and Much to Lose.” The article takes aim at Common Core’s requirement that kindergartners learn to read:

Many children are not developmentally ready to read in kindergarten, yet the Common Core State Standards require them to do just that. This is leading to inappropriate classroom practices.

When children have educational experiences that are not geared to their developmental level or in tune with their learning and cultures, it can cause them great harm, including feelings of inadequacy and confusion.2

Keith Poston and other Common Core supporters say that we need to hold all students to the same standards. Such comments ignore the question of appropriateness and misconstrue the position of Common Core critics.

Why is this important? Why should we care that Common Core Standards are age-appropriate and take into account a child’s needs and developmental abilities?

In her presentation at the Notre Dame Common Core Conference in September 2013, Child Psychologist, Dr. Meghan Koshnick answered that question in one word – stress.3

Instead of thinking about what’s developmentally appropriate for kindergartners, they are thinking [college] is where we want kindergarteners to end up, so let’s back track down to kindergarten and have kindergarteners work on these skills from an early age. This can cause major stress for the child because they are not prepared for this level of education.

Is this stress real? Parents who have a child in K-3 know what I’m talking about. Anyone who attended last year’s public hearing on Common Core remembers the high number of parents who shared their frustrations with how their children were being affected by the Common Core Standards. Common Core math and English standards were clearly becoming a growing source of stress for children and parents alike.

I ask: Is this what we want school to be? Do we want standards that fail to consider the age, abilities and background of our students and treat all students the same? Public School Forum and other pro-Common Core organizations think so. They say changing the standards will diminish rigor.

Keith Poston and others fail to understand that implicit in rigor is the concept of appropriateness. Ensuring standards are age-appropriate is one of the tasks the Legislature delegated to the Academic Standards Review Commission. The statutes say “conduct a comprehensive review and propose modifications to ensure …”4 meaning the legislature expected changes (i.e., repeal and revisions) to the standards to be part of the normal process.

Yes, students should be held to the same standards. However, it’s assumed that those standards are rigorous, understandable and age-appropriate.

To assert that ASRC members shouldn’t contemplate changes to the standards is to misread the legislation that created the commission. Such thinking disregards the opinions of hundreds of child development professionals who are deeply troubled by how much Common Core asks K-3 children to master. Worst of all, those who advocate such a position ignore the very real academic and emotional harm Common Core inflicts on students of all ages, especially those in grades K through 3. These consequences should make us all stop and ask: Is this the type of education we want for our children?

Part II: “Teacher Voices” and Common Core

In “Maintaining rigor and listening to teachers in the debate over academic standards,” Keith Poston of the Public School Forum argues against changing the Common Core math and English standards, since he believes members of the state’s Academic Standards Review Commission (ASRC) are working to weaken the standards. In the second half of his article, Poston talks about the supposed strong support teachers have for the Common Core Standards and that teacher voices need to be a significant part of the public discussion over the standards. Results of an “Educator Survey” conducted by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction have helped to form Poston’s views. The survey asked respondents whether specific Common Core math or English Language Arts standards were acceptable or should be revised.

Poston writes:

Out of more than 850 standards covered by the survey, over 450 standards (more than half) were endorsed by at least 90 percent of responding educators, meaning fewer than 10 percent of respondents felt revisions were needed. Approximately 775 standards (around 87.5 percent) were endorsed by at least 80 percent of responding educators, meaning fewer than 20 percent felt revisions were needed. There was not a single standard for which a majority of responding educators felt revisions were needed. . . .

Rather than recognizing the strong support for the standards reflected in the survey results, some commissioners speaking at the January meeting attempted to dismiss the survey because they felt there were too few responses. The survey covered every K-8 grade in mathematics and ELA, as well as Math I, Math II, Math III, Grade 9-10 ELA, and Grade 11-12 ELA. Most individual grade levels in each subject received several hundred responses.5

Two issues emerge from these paragraphs. First, I also agree that teachers should have a strong voice in the public discussion over Common Core Standards. In fact, up to this point, I believe they have been largely shut out of that discussion, but that’s another story. In my view, in their eagerness to assert their position, Poston and other Common Core advocates have been quick to jump on the results of the Educator Surveys. A closer look reveals the surveys have numerous flaws.

We are told the survey results represent the views of teachers. But do they? According to the DPI contact who administered the survey:

…the surveys were made available to educators on the NCDPI web site and through communications sent from NCDPI through teacher listservs, superintendent and principal messages, RESA presentations, UNC System listerve, and curriculum and instruction leader meetings. The survey was distributed by DPI. The surveys were launched October 20, 2014 and ended December 31, 2014.6

Who was supposed to complete the survey? Again, according to DPI:

The survey was open to any educator who wished to participate, regardless of their current position. We did not require the survey respondent to indicate that they had specific knowledge of the standards on which they commented.7

So it appears anyone could complete an “Educator Survey.” If you’re an educator, you could be a teacher, but you could also be an administrator, school nurse, library assistant, custodian, school secretary or just about anyone who works in a school. Anyone could respond to the questions about Common Core Standards. You needn’t possess any special knowledge or expertise of the standards to comment on them. It appears you could submit your comments on standards for any grade. For example, if you were a third-grade teacher, you could complete the survey for high school math. Likewise, a school nurse might do the same. It also appears you could submit more than one survey. In fact, as many as you wish.

Why is this important? All these shortcomings make it difficult to say the surveys reflect the views of teachers. It may reflect the view of some teachers. However, there is no definitive way to know. The survey instrument pools the views of many educators and lacks the ability to separate out the views of teachers.

Despite the obvious limitations, Poston remains undeterred. He writes that it would be “unfortunate” if the commission failed to give serious weight to “educators who offer the most credible voices on the acceptability of the standards.” Poston takes issue with some members of the Academic Standards Review Commission who criticized the survey for the number of responses.

DPI officials said they received 8,703 completed surveys. As previously mentioned, however, there is no way of knowing what represents teacher opinion or merely the opinion of educators. A quick review of the surveys shows approximately 360 people responded to each of the individual standards – not a very large number.8

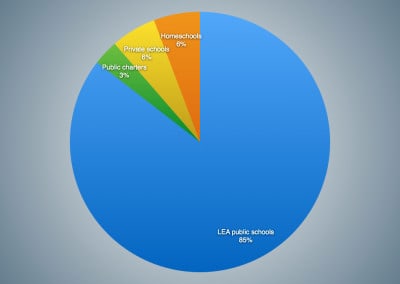

Of course the question becomes: to what universe do the respondents belong, teacher or public school employees? Keith Poston says these are teacher responses – though there’s no way to discern how many – but let’s assume they all are. If all the surveys are completed by teachers, they represent approximately 9 percent of all teachers. If the results merely represent the views of “educators’ – and the term educator is synonymous with public school employee – the sample responses represent 4.9 percent of all employees.9

The other problem in this scenario is that even if the results represented exclusively teacher views, no steps have been taken to ensure the population is representative of all teachers. As such, the surveys are merely representatives of those individuals who chose to respond. The results may be interesting, but the results cannot be said to have been derived scientifically. Worse yet, that fact does not seem to have been reported.

So how do teachers feel about Common Core Standards? Obviously, teacher surveys on the subject would be helpful. That’s exactly what the Civitas Institute did in 2013. We developed a brief questionnaire asking teachers to respond to various questions about Common Core. The survey – admittedly unscientific – was distributed via Survey Monkey. It was sent to teacher email addresses obtained from the North Carolina Department of Public instruction. The survey generated 1,700 responses from 71 different LEAs. What did we find? Briefly the findings are instructive. (If you’d like to learn more about the results, click here):

Teachers are conflicted about Common Core. Many may like the standards, but teachers have reservations about individual standards and how the standards are being implemented.

- 62 percent of teacher respondents favored proposals to slow down or halt the implementation of Common Core Standards; 38 percent oppose proposals to do so.

- 55 percent of respondents rated their schools’ preparation for Common Core Standards as “average, weak, or poor.”

- 65 percent of respondents approve of the decision to implement Common Core Standards.

- Less than half of all respondents expressed confidence that Common Core Standards would help to improve student achievement.

Civitas published the responses to the Common Core questions. However we also published all the comments of individual teachers. (See collected responses here). Teachers both praised and criticized the standards. Here are a few teacher comments.

Teachers Praise Common Core:

“Common Core is great, but it’s been rolled out poorly in our district.”

“I believe NC needs to ‘catch up’ with the rest of the nation. This year has been tough with higher expectations, but in a few years it will balance out.”

“I think the principle behind Common Core is great. I just don’t think everything should be tied to testing. Our students are tested to death.”

Teachers Criticize Common Core:

“Common Core seems to be just another ‘Flavor of the Month’ and within five years it will be replaced.”

“[Common Core] teaches to the middle and puts low expectations on all students.”

“… we were not given proper materials to implement these standards in our classrooms. We have been flying the airplane while building it.!”

Teachers on Resources for Common Core:

“We do not have the money to change all the materials and resources to align with Common Core.”

“The lack of materials has placed an almost impossible burden on teachers.”

“What textbooks?!”

On Teacher Input for Implementing Common Core:

“I was not aware teachers had any say in this … As far as I know the only ones making any decisions are the clueless politicians in Raleigh who have no idea what actually goes on in schools.”

“We had NO input [we were ] told this is what we are doing.”

“Teachers have been involved?”

As you can see, the results reflect a range of views on Common Core. They also offer a perspective far different from that reported in the results of the educator surveys.

Everyone agrees North Carolina public schools should have high academic standards. To that end, the General Assembly charged the Academic Standards Review Commission with reviewing the Common Core math and English Language Arts standards and ensuring that North Carolina Standards “increase academic achievement, meet and reflect North Carolina priorities, are age and developmentally appropriate, are understandable to parents and teachers” and “among the highest standards in the nation.”10

These are ambitious but important tasks, necessitated by unending controversy and a widely shared belief that Common Core did an end run around the democratic process. In 2010, when the State Board of Education adopted the Common Core Standards there was no discussion of the merit or impact of the standards. Questions continue to arise regarding the standards themselves and the lack of research that supports them. Moreover, many believe Common Core transfers the locus of power over education policymaking from the states to Washington and unelected bureaucrats.

The ASRC was formed to address the ongoing controversy and provide a roadmap for the way forward. Claims that the ASRC is “ignoring the teacher’s voice” and “setting the stage for a watering down of North Carolina’s academic standards” have no basis in fact and are unequivocally false. They also ignore ASRC’s responsibility to “propose modifications” to ensure the standards meet the criteria established in SL 2014-78.

A discussion of differing honest opinions enriches the policy process, something our Common Core debate badly needs. Narratives based on baseless accusation and misunderstanding of the policy process generate more heat than light. I hope we can commit ourselves to the former. The stakes are too high for anything less than effective, fair dialogue.